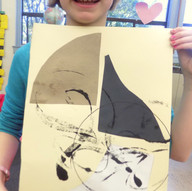

Louise Nevelson Russia/US 1899–1988

Louise Nevelson was the Grand Dame of Sculpture. With her larger than life persona and striking look, she was a force of nature. She came to the United States as a child with her family, settling first in Rockland, Maine. At age twenty she went to New York to study voice and drama as well as painting and drawing. She attended the Art Students League in 1929 and 1930, then traveled to Munich to study with Hans Hoffman. Two years later she was working as an assistant to Diego Rivera, who introduced her to Pre-Columbian art. She worked for the WPA painting and sculpture divisions until 1939 creating murals. For several years, the impoverished Nevelson and her son walked through the streets gathering wood to burn in their fireplace to keep warm; the firewood she found served as the starting point for the art that made her famous. Her large scale works are known for using up-cycled materials. In 1954, her street in New York's Kips Bay was among those slated for demolition and redevelopment, and her increasing use of scrap materials in the years ahead drew upon on refuse left on the streets by her evicted neighbors Usually created out of wood, her sculptures appear puzzle-like, with multiple intricately cut pieces placed into wall sculptures or independently standing pieces, often 3-D. One unique feature of her work is that her figures are often painted in monochromatic black or white. In 1962 she made her first museum sale to the Whitney Museum of American Art. That same year, her work was selected for the 31st Venice Biennale and she became national president of Artists' Equity, serving until 1964. Her work is seen in major collections in museums and corporations.She remains one of the most important figures in 20th-century Art. She received many awards in her career, including the American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal, the Brandeis University Creative Arts Award in Sculpture, an honorary degree from Harvard University, an Honorary degree from Rutgers University, a fellow of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and the National Medal of Arts. At the time of her death, her estate and body of work were estimated at 100 million. Even though her work was groundbreaking, she refused the title of “ Feminist artist”, feeling that it diminished her work and preferred to be known simply as an artist.